What a month October has been down here in the heart-shaped island, with not one, but two SCBWI TAS events.

Sheryl Gwyther Talk

7 October

Seven children’s book creators turned up to ‘Shippies’ Hotel at Battery Point on 7 October to hear Assistant Regional Advisor and Queensland Coordinator, Sheryl Gwyther, present about her dazzling new middle-grade novel, Sweet Adversity (Harper Collins). Sheryl spoke about her long and winding road to publication and how membership of SCBWI opens access to publishers, and supports networking, friendships, knowledge and collegial support nationally and globally.

Sheryl is a long term friend of Tasmania’s creatives and its wild natural environment and she is welcome back any time to continue to inspire our local members.

‘SHINING A LIGHT ON TASMANIAN TALENT’ - SCBWI TAS PROFESSIONAL DAY 27 OCTOBER

Our first SCBWI TAS conference was judged outstanding success by all who attended. With the help of a $5,000 grant from Arts Tasmania, we were able to bring publisher, Clare Hallifax (Omnibus, Scholastic), publishing consultant, Maryann Ballantyne, and literary agent, Alex Adsett to the conference.

Our guest publishers and agent conducted manuscript assessments throughout the conference and on the following day at the Tasmanian Writers Centre.

Susanne Gervay opened the conference and Terry Whitebeach acknowledged Country. Clare Hallifax delivered the keynote address on publishing today. Tony Flowers and Christina Booth spoke about the illustrators’ craft and the challenges of illustrating a narrative.

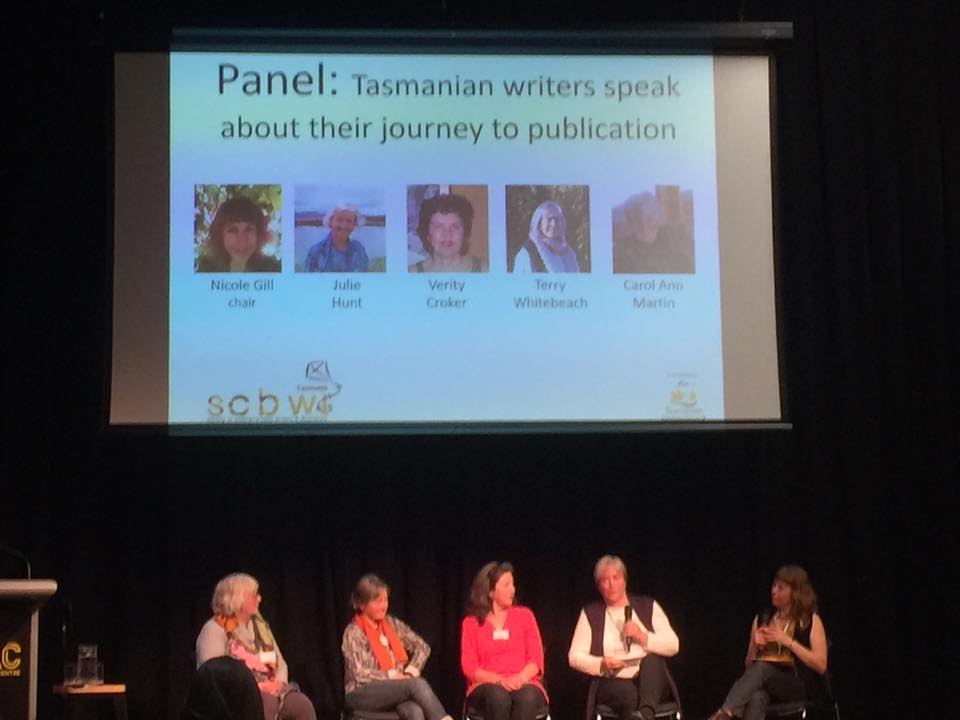

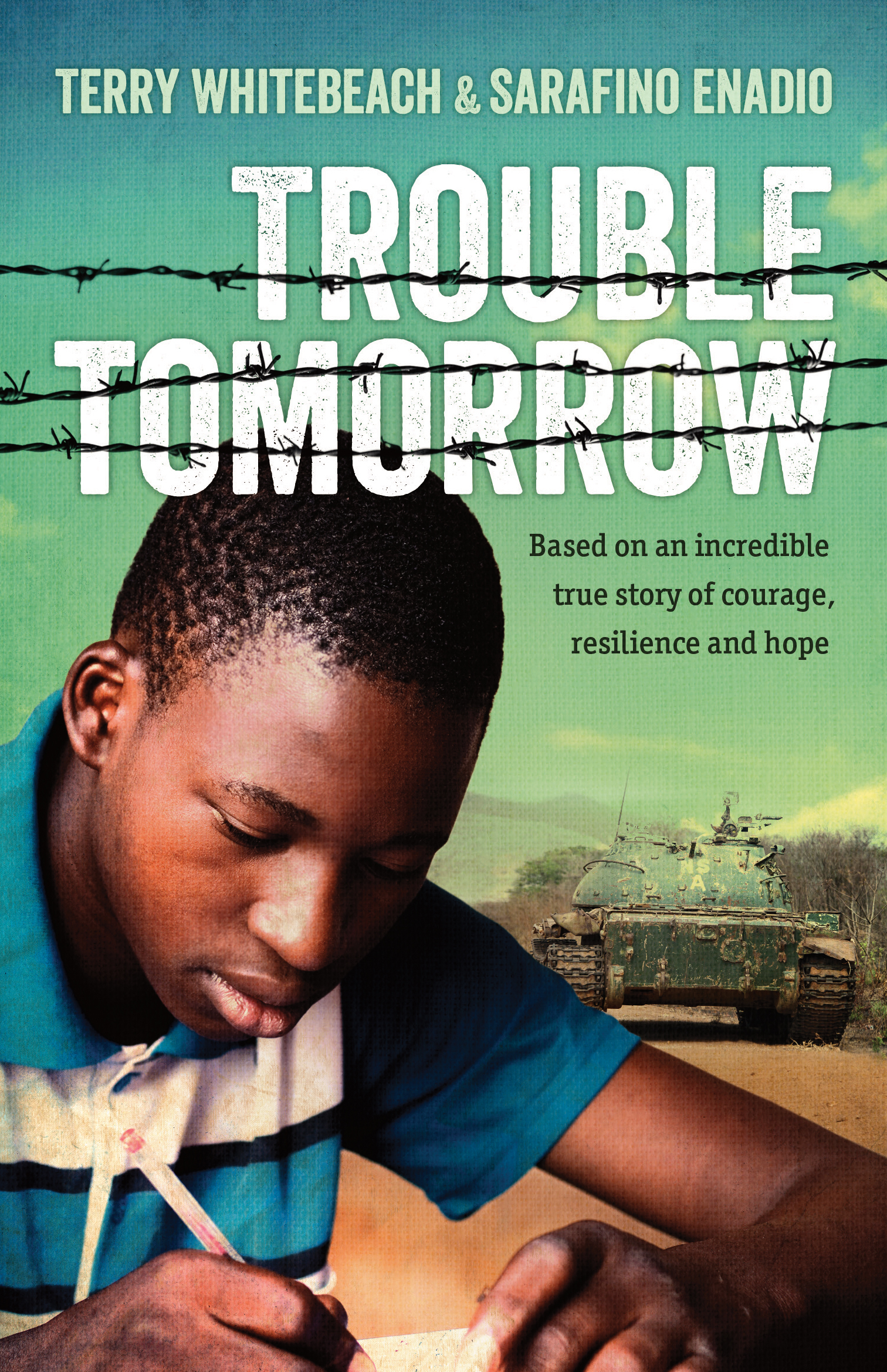

Alex spoke about what a literary agent does, and 10 top tricks and traps of publishing contracts. Christina then interviewed a panel of talented local illustrators, Alyssa Bermudez, Bronwyn Houston and Aurore McLeod and Tony Flowers. Nicole Gill then chaired a panel of eminent Tasmanian children’s writers that comprised Julie Hunt, Verity Croker, Terry Whitebeach and Carol Ann Martin.

Afternoon sessions included ‘Approaching an agent or publisher’ and ‘A bookseller’s perspective on promoting Tasmanian talent,’ presented by Clive Tilsley, FullersBookshop. Susanne chaired the ‘Working with a publisher’ panel that included writer, Emily Conolon, and publishers. The final session was ‘How SCBWI connects authors and illustrators to the industry

This was the first time SCBWI TAS has attempted a conference and we were delighted by the support of over 40 children’s book creators. The feedback on the publisher and agent information and manuscript assessments has been overwhelmingly positive, and we look forward to many more Tasmanian writers and illustrators getting published as a direct and indirect result of attending this conference and their SCBWI membership.

Thanks to all who made this conference such a blast – Clare Hallifax, Maryann Ballantyne, Alex Adsett, Christina Booth, Marion Stoneman, Terry Whitebeach and the Tasmanian Writers Centre, Warren and Jemima Kinman, Aurore McLeod, and all who brought morning/afternoon tea and helped us at the Moonah Arts Centre and the Tasmanian Writers Centre.